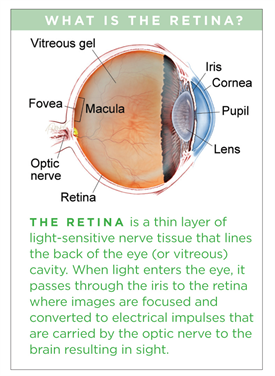

Central retinal vein occlusion, also known as CRVO, is a condition in which the main vein that drains blood from the retina closes off partially or completely. This can cause blurred vision and other problems with the eye.

Symptoms

Mild CRVO may show no symptoms. However:

- Many patients with CRVO have symptoms such as blurry or distorted vision due to swelling of the center part of the retina, known as the macula.

- Some patients have mild symptoms that wax and wane, called transient visual obscurations.

- Patients with severe CRVO and secondary complications such as glaucoma (a disease characterized by increased pressure in the eye) often have pain, redness, irritation and other problems.

Causes

Most patients with CRVO develop it in one eye. And, although diabetes and high blood pressure are risk factors for CRVO, its specific cause is still unknown. What we do know is that CRVO develops from a blood clot or reduced blood flow in the central retinal vein that drains the retina. And we have learned that a large number of conditions may increase the risk of blood clots. Some eye doctors advise testing for them. However, it is not certain how these health conditions are related to CRVO—and some of them, if diagnosed, have no agreed-to or necessary recommended treatment.

Many eye doctors do not advise testing for a CRVO in one eye, but do recommend a visit with a family doctor to be sure there is no diabetes or high blood pressure.

CRVO that occurs in both eyes at the same time can be related to systemic disease; in these cases, a tendency toward abnormal blood clotting is definitely more common and medical testing to detect so-called “hypercoagulable states” is indicated. While some eye doctors coordinate such testing, most refer patients to their family doctors, internists, or hematologists (physicians specializing in diseases of the blood) for testing.

Diagnostic Testing

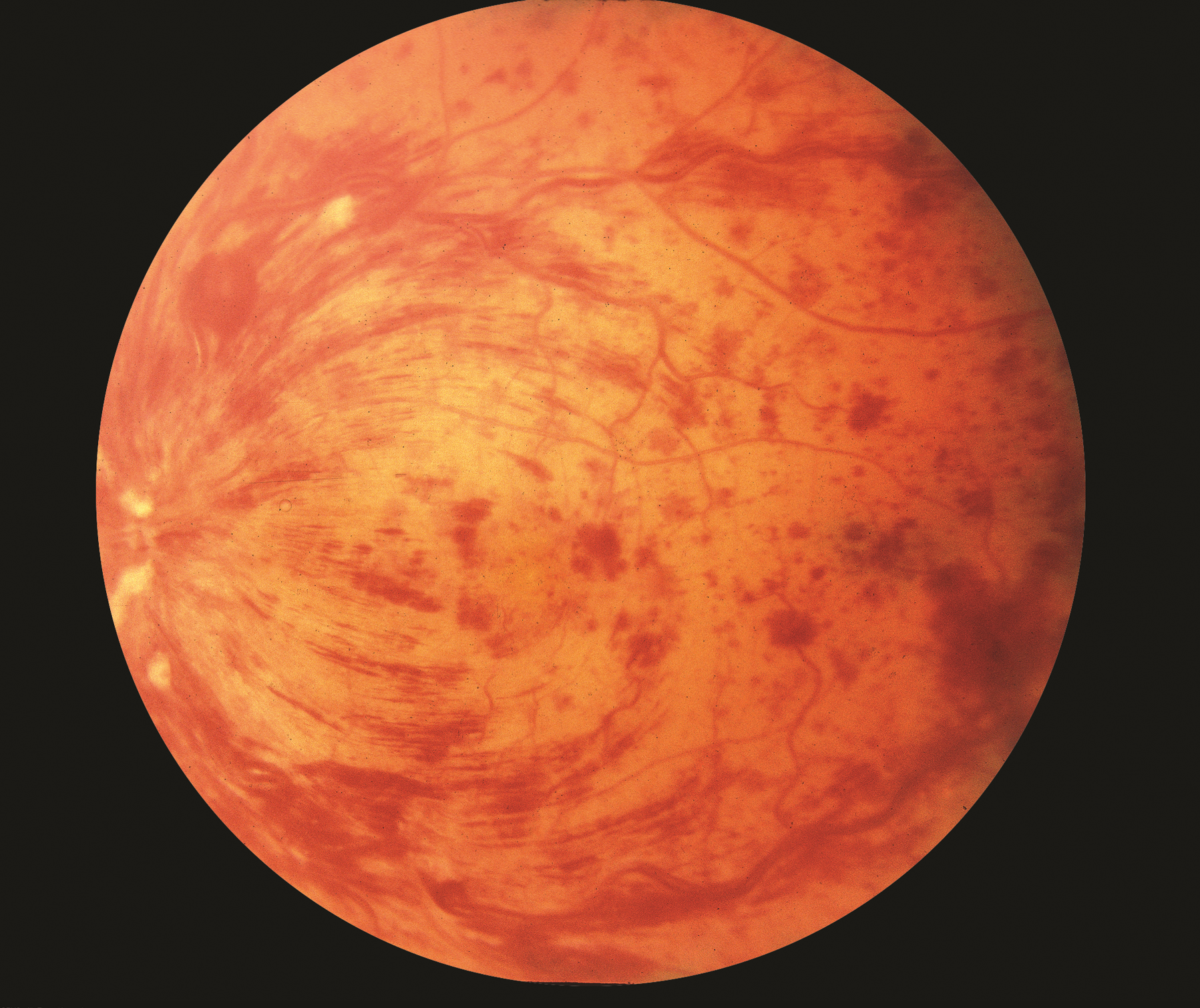

CRVO is typically a clinical diagnosis—that is, one based on medical signs and patientreported symptoms. When a retina specialist looks into the eye, there is a characteristic pattern of retinal hemorrhages (bleeding) and a diagnosis is made (Figure 1).

Common conditions that can take on an appearance of CRVO include diabetic retinopathy (retina disease) and retinopathy related to low blood counts, such as anemia and thrombocytopenia (a deficiency of blood platelets).

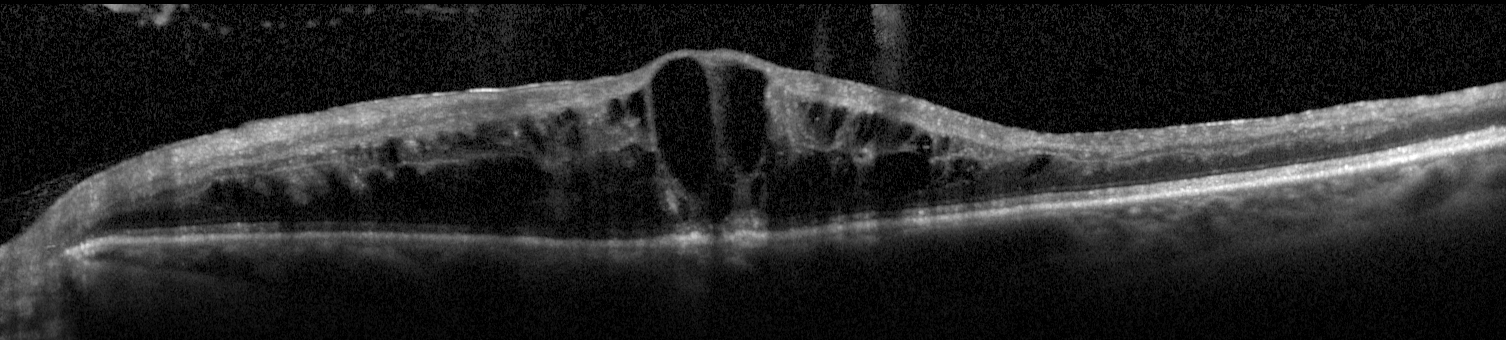

Swelling of the center of the retina, called macular edema is common, and to detect this and measure the amount of swelling, an optical coherence tomography (OCT) image is often obtained (Figure 2). To help distinguish CRVO from conditions that may mimic it, and to assess closure of small blood vessels, or to search for or confirm growth of new abnormal vessels, fluorescein angiography (FA) imaging may be performed.

Treatment and Prognosis

CRVO has a better prognosis in young people. In older patients who receive no treatment, about one-third improve on their own, about one-third wax and wane and stay about the same, and about one-third get worse. If there is macular edema, it may improve on its own.

In patients with CRVO, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is elevated; this leads to swelling as well as new vessels that are prone to bleeding. The most common treatment, based on results from powerful randomized clinical trials, involves periodic injections into the eye of an anti-VEGF drug to reduce the new blood vessel growth and swelling. Anti-VEGF drugs include bevacizumab (Avastin®), ranibizumab (Lucentis®), and aflibercept (Eylea®).

Although anti-VEGF drugs reduce the swelling, they are not a cure. As the drug leaves the eye and moves into the bloodstream, the effect in the eye wears off, so re-injection is often needed. A rare lucky patient needs only one injection, but the norm is a series of periodic injections over the course of a few years.

Ischemic (pronounced is KEY mick) and Non-ischemic CRVO: CRVO comes in 2 types

- Non-ischemic CRVO—a milder type characterized by leaky retinal vessels with macular edema

- Ischemic CRVO—a more severe type with closed-off small retinal blood vessels

Patients with ischemic CRVO have worse vision with less chance for improvement. They have a tendency for the eye to cause new blood vessels to grow—and in the front of the eye, these new vessels can clog the outflow of normal eye fluids. The eye pressure goes up and glaucoma develops. In the back of the eye, new blood vessels may cause bleeding.

When there is ischemic CRVO with new vessels, anti-VEGF injections lead to prompt, but often temporary, control of the new vessels. Laser treatment tends to offer a more permanent effect. In some cases, both treatments are used.

Non-ischemic CRVO can worsen and become ischemic, so when CRVO is diagnosed, monthly checkups are initially recommended.

It’s important to note that early detection of macular edema or abnormal blood vessels is important; most patients can avoid severe vision loss if treatment is begun before substantial damage develops in the eye.

Authors

Thank You to the Retina Health Series Authors

Sophie J. Bakri, MD

Audina Berrocal, MD

Antonio Capone, Jr., MD

Netan Choudhry, MD, FRCS-C

Thomas Ciulla, MD, MBA

Pravin U. Dugel, MD

Geoffrey G. Emerson, MD, PhD

Roger A. Goldberg, MD, MBA

Darin R. Goldman, MD

Dilraj S. Grewal, MD

Larry Halperin, MD

Vincent S. Hau, MD, PhD

Suber S. Huang, MD, MBA

Mark S. Humayun, MD, PhD

Peter K. Kaiser, MD

M. Ali Khan, MD

Anat Loewenstein, MD

Mathew J. MacCumber, MD, PhD

Maya Maloney, MD

Hossein Nazari, MD

Larry Halperin, MD

Vincent S. Hau, MD, PhD

Suber S. Huang, MD, MBA

Mark S. Humayun, MD, PhD

Peter K. Kaiser, MD

M. Ali Khan, MD

Anat Loewenstein, MD

Mathew J. MacCumber, MD, PhD

Maya Maloney, MD

Hossein Nazari, MD

Oded Ohana, MD, MBA

George Parlitsis, MD

Jonathan L. Prenner, MD

Gilad Rabina, MD

Carl D. Regillo, MD, FACS

Andrew P. Schachat, MD

Michael Seider, MD

Eduardo Uchiyama, MD

Allen Z. Verne, MD

Yoshihiro Yonekawa, MD

Editor

John T. Thompson, MD

Medical Illustrator

Tim Hengst

Downloads

Copyright 2016 The Foundation of the American Society of Retina Specialists. All rights reserved.